No one likes to pay taxes. That’s just one of life’s truisms. While it’s ill-advised (and illegal!) to avoid paying your taxes, fortunately, there can be a few ways to lessen the burden. For instance, you can move to a state with zero income tax or low property tax. Or you can donate up to 60% of your adjusted gross income to charity. Another option to reduce your tax bill could be buying an ETF instead of a similar mutual fund. How so? It’s all about their structure.

How do investments generate a tax bill?

Anytime a holding is sold, it triggers a taxable event. That’s the case whether you own shares of your favorite company, invest in a mutual fund, or buy an ETF. However, if you sell your shares at a loss, you don’t owe any capital gains tax (because you did not have a gain!). But if your investments have appreciated, you will owe the IRS on that gain.

Unfortunately, a sale isn’t the only time you may have to pay Uncle Sam. There are several instances when current investments generate taxes too. The first is if you receive a dividend payout. The second is if you hold a mutual fund and receive a distribution. Luckily, the same is not generally true when you own ETFs.

How can investors get hit with a tax bill while holding a mutual fund but not an ETF? We explain.

How do ETFs reduce the tax burden?

Understanding how ETFs trade is critical to grasp why they can generally be more tax-efficient than similar mutual funds. What do we mean by similar? Comparing an ETF and a mutual fund that track the same index. For example, an S&P 500 index mutual fund to an S&P 500 ETF. What is not similar? Comparing an S&P 500 ETF to a corporate bond mutual fund.

Let’s get back to tax efficiency and set the scene:

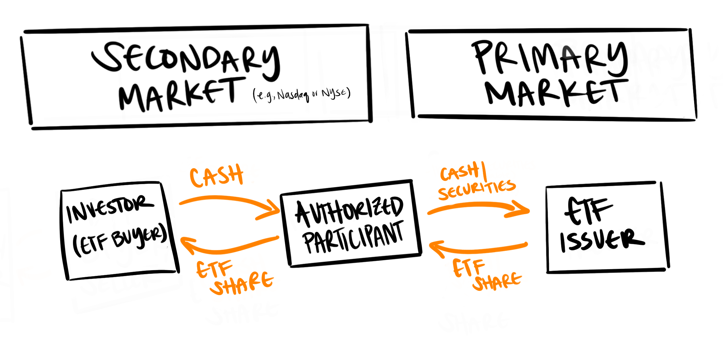

Where ETFs trade: There are two types of markets upon which ETFs trade. ETFs are created and redeemed on the primary market. Individual or institutional investors do not generally trade shares on the primary market. Instead, the secondary market is where investors—like you—buy or sell ETF shares. (Stocks trade on a secondary market too!)

Who participates in ETF trades? There are three parties involved with ETFs’ creation and redemption trading:

- ETF Issuer—the creator/manager of the ETF

- Authorized Participant (AP)—think of the AP as the middle person between the primary and secondary markets

- Investor—that’s you or your clients, the ETF buyer or seller

The buying process

In the buying process, the ETF Issuer sells ETF shares to the AP and receives cash on the primary market. Then the AP sells ETF shares to an investor, who gives the AP cash. This transaction happens on the secondary market and works exactly like the process of buying individual stocks.

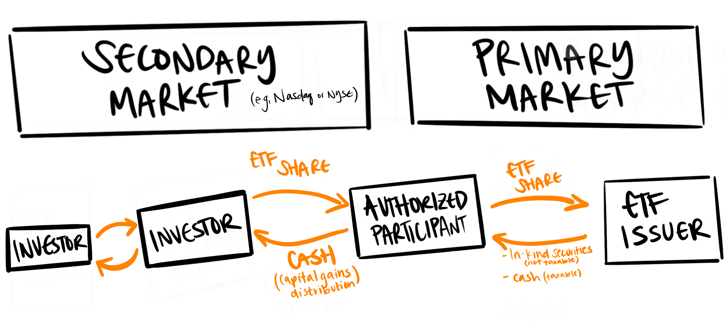

The selling process

The selling process works somewhat in reverse, with most trading occurring on the secondary market. Investors who want to liquidate their ETF shares sell them on an exchange—like the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq—to another investor. This transaction does not impact the underlying holdings within the ETF. In other words, the Issuer doesn’t need to sell any of the underlying securities.

This is a key difference with similar mutual funds. Mutual funds may need to sell underlying securities to raise cash if investors want to redeem their shares, so they generally generate capital gains or losses for the current fund holders. As a general matter, ETFs do not, so current investors may not be hit with a tax bill. (But recall, since the buyer sold an investment, that sale may trigger capital gains and will have a tax impact if their ETF appreciated—just like it would with an appreciated stock sale.)

What happens when an AP redeems shares with an Issuer? ETF trading occurs on the primary market between the AP and Issuer. In some instances, the Issuer may deliver the securities “in-kind,” rather than via cash, to the AP. Since, in this situation, there is no sale of securities, there’s no capital gain. Further, this “in-kind” exchange can potentially reduce a future potential tax burden. During the transfer, the Issuer could hand over securities with the lowest cost basis and hold the ones closest to the current market price. It’s like stepping up the cost basis on a house in an estate transfer. So when you sell that1 home, your basis could be close to the selling price, potentially resulting in a minimal gain and lower tax bill.

However, if the AP exchanges ETF shares for cash or the Issuer needs to buy or sell specific securities, this could trigger capital gains or losses. Changing the underlying holdings typically occurs if an ETF tracks an index. Suppose the target index is rebalancing its holdings. In that case, the ETF may need to buy and sell securities, which could result in a taxable event.

Investor control is one benefit of ETFs

As we said at the outset, if an investor sells a holding, a tax event may occur, and the IRS may come collecting if there are capital gains. But because typically ETFs tend not to sell their underlying securities, the ETF shareholders generally do not get hit with a tax bill until they sell their positions in most circumstances. We consider this to be one of the many benefits of choosing an ETF over a similar mutual fund. Want to know other benefits?

Related Posts

Market Predictions are Futile

Mann on the Street

A few years ago I got to hear JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon give a talk at a conference in Hong Kong,...

The Hidden Cost of Chasing Trends

Identifying a major investment trend before it hits the mainstream feels like finding buried...

How Can ETFs Help Investors Avoid The Wash Sale Rule?

Selling an investment at a loss can be smart tax planning—but only if you don’t accidentally give...

Interested in more?

Get our popular newseltter delivered to your inbox every month.

Search the Insights Blog

How to invest with us

Click the button below to learn how you can get started with Motley Fool Asset Management