Traditionally recessions are characterized by slowing economic growth, job loss, rising unemployment, and reduced consumer spending. As a worker, you may fear job loss. Or, as a business owner, lower consumer spending may worry you. As a manufacturer, slowing growth may derail your output. So sure, there are many things to worry about in a recession. But what about as an investor?

That answer is a little trickier.

The recession watch

Waiting to see if the economy hits a recession has become almost as popular as the anticipation of Y2K at the turn of the century. However, with Y2K, the outcome was…well…happily uneventful, with the most significant impact being pantries full of extra canned goods! So this year, will expectations of a 2023 recession fizzle out like Y2K, or will the forecasted 70% odds manifest into this feared economic event?1

Neither do we—nor does anyone else—know the answer. However, we don’t think what the powers-that-be call the economy is as important as what the current environment means for investors. Because regardless of if the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) assigns the "recession" moniker, investors still expect slowing GDP growth—whether it moves negative and remains there doesn’t change the fact that growth is slowing. And consumer confidence is down in the dumps—because even though wages have risen, inflation has stolen those higher paychecks and then some, so real wealth has fallen. Even CEOs feel the "blues" as corporate profits fall. Sounds rather depressing, right?

But here’s the optimism: The stock market is not the economy.

Recession depression

Before we explain how the stock market and economy differ—and, more importantly, why it matters to investors—we'd like to show what could be in store should a recession occur.

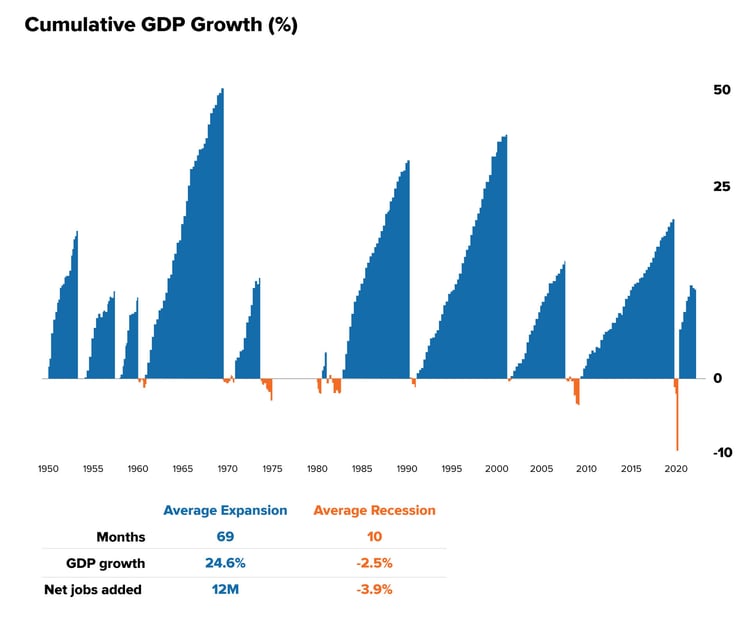

Historically the average recession has lasted 10 months, with negative GDP growth of 2.5% and a loss of 3.9 million jobs.2 Without a doubt, it’s a painful period. Fortunately, recessions have tended to be short-lived, while expansions tended to be longer (69 months on average), created over 10 million jobs, and grew the economy by nearly 25%.3

Sources: Capital Group, National Bureau of Economic Research, Refinitiv Datastream. Chart data is latest available as of Jun. 30, 2022 and shown on a logarithmic scale. The expansion that began in 2020 is still considered current as of Jun. 30, 2022 and not included in the average expansion summary statistics. Since NBER announces recession start and end months rather than exact dates, we have used month-end dates as a proxy for calculations of jobs added. Nearest quarter and values used for GDP growth rates.

Sources: Capital Group, National Bureau of Economic Research, Refinitiv Datastream. Chart data is latest available as of Jun. 30, 2022 and shown on a logarithmic scale. The expansion that began in 2020 is still considered current as of Jun. 30, 2022 and not included in the average expansion summary statistics. Since NBER announces recession start and end months rather than exact dates, we have used month-end dates as a proxy for calculations of jobs added. Nearest quarter and values used for GDP growth rates.

But as we said, the economy and the stock market are not one and the same. So here's how they differ.

Bugs Bunny and Roger Rabbit: Both bunnies, different personalities

Many investors believe that the economy and the stock market are synonymous. And while they do interact, most of the time, they act differently. For example, let’s compare their makeup. Services comprise 84% of U.S. employment and 59% of U.S. GDP but are only 38% of the share in the S&P 500.4 In other words, what drives the economy is not the same as what drives the stock market. Obviously, they overlap at some point, but they're not wholly congruent. This is most evident by the real returns of the stock market compared to GDP growth. (Note: When we talk about real, it means adjusted for inflation.)

Source: NYU, FRED

Source: NYU, FRED

The chart shows that the stock market typically has delivered more robust returns than GDP growth. In every decade except for two—the 1970s and the 2000s—real stock returns were significantly higher. The 2000s are interesting because the stock market faced two adverse events during that decade—the tech bubble bursting and the global financial crisis. Yet despite those significant events and resultant recessions, the decade was only down 1% and was followed by a solid decade in the 2010s.

The other way that the stock market and economy differ is timing. The stock market tends to be a leading indicator of the economy. This means the stock market tends to fall—or rise—before seeing a similar economic trend. Or said another way, the stock market looks ahead while most reported economic data look behind.

.jpg?width=750&height=474&name=Stocks-have-typically-been-a-leading-indicator-of-the-economy%20(1).jpg) Source: Capital Group, Federal Reserve Board, Haver Analytics, National Bureau of Economic Research, Standard and Poor's. Data reflects the average of completed cycles in the U.S. from 1950 to 2021 indexed to 100 or each cycle peak. Industrial production measures the change in output by manufacturers, mines, and utilities and is used here as a proxy for the economic cycle. Past results are not predictive of future periods.

Source: Capital Group, Federal Reserve Board, Haver Analytics, National Bureau of Economic Research, Standard and Poor's. Data reflects the average of completed cycles in the U.S. from 1950 to 2021 indexed to 100 or each cycle peak. Industrial production measures the change in output by manufacturers, mines, and utilities and is used here as a proxy for the economic cycle. Past results are not predictive of future periods.

So, should we fear a recession?

Fearing a recession is natural. As workers or business owners, you can't help but worry. But as investors, a recession tends to mark a turning point. How so?

The announcement of a recession trails what’s already been happening in the economy. In other words, sentiment, business conditions, GDP growth, hiring, and other indicators have already fallen or turned negative. So when the NBER calls the recession, it's also typically already reflected in stocks.

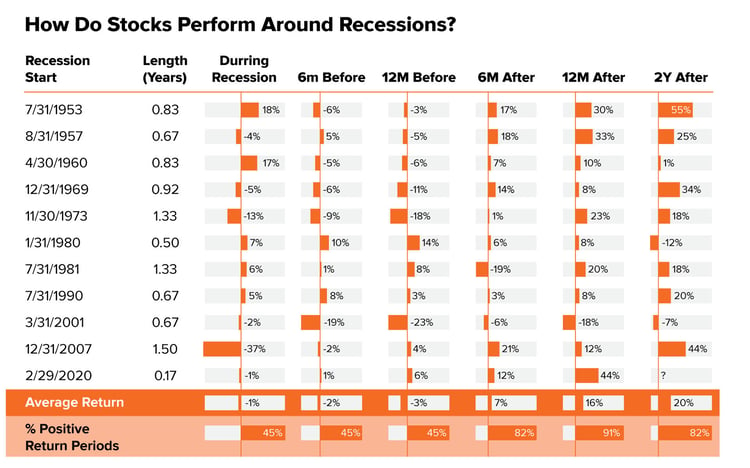

This chart shows historical stock market performance before, during, and after a recession. The worst price performance has been the year before a recession, with an average return of -3%. During a recession, the market was also down 1% on average. But after a downturn, stocks historically tended to be positive. Case in point: Two years following a recession, price returns were positive 82% of the time.5

Source: Darrow Wealth Management, YCharts, NBER. Cumulative price return of the S&P 500 during past recessions. Past performance not indicative of future results.

Source: Darrow Wealth Management, YCharts, NBER. Cumulative price return of the S&P 500 during past recessions. Past performance not indicative of future results.

So when you consider all of this, yes, a recession is a concern. But by the time of an official announcement, the market likely already should reflect much of the bad news. History shows that this has been true and goes even further. It also tends to signal that the market should be nearing bottom or should already have made the turn-up—a seemingly positive sign. So weirdly, investors should feel relief when the NBER declares “recession” because they’ve already been feeling the pain, and an upturn may be coming shortly.

.jpg?width=750&height=469&name=Market-performance-after-recession-announcementMFAM%20(3).jpg)

This is the second installment in our series, 2023 Outlook: Recession. If you missed the first, “Are We in a Recession?” check it out here.

Footnotes

1Bloomberg survey, Dec. 2022

2Capital Group, data as of June 30, 2022

3Capital Group, data as of June 30, 2022

4Apollo Academy and BlackRock Investment Institute, with data from Refinitiv Datastream and U.S. Bureau of Economic analysis. Aug. 2022. S&P 500 data uses analyst earnings estimates for the full-year 2022 and groups S&P 500 sectors into goods and services, excluding financials and energy. GCP data is based on 2022 Q1 and Q2.

Related Posts

All That Glitters

McFaddin on the Markets

Now that the first month is behind us, and we have 11 more to keep us busy, I think now is as good...

What is a Bond Ladder?

A bond ladder is a fixed income strategy that involves owning a series of individual bonds with...

Looking Beyond the 60/40 Portfolio

The 60/40 portfolio, consisting of 60% stocks and 40% bonds, has long been the standard balanced...

Interested in more?

Get our popular newseltter delivered to your inbox every month.

Search the Insights Blog

How to invest with us

Click the button below to learn how you can get started with Motley Fool Asset Management