Recessions are an economic—not a stock market—phenomenon. Yet, since the economy and the market, while not the same, are intertwined, investing during a contraction may require tweaks to your portfolio. What do we mean by “tweaks”? We generally aren’t implying a wholesale strategy change or a “shoot now, ask questions later” mentality. Instead, investing before, during, and after a recession is about reassessing asset allocation and reevaluating stock positions to take advantage of rare opportunities to set up wealth for growth when things turn around.

Reassess asset allocation

88% of a portfolio’s return comes from asset allocation —the mix of stocks, bonds, and alternative assets that make up a portfolio.1 Asset allocation is a function of an investor’s goals, time horizon, and risk, among other factors. So how do investors determine what could be the “right” allocation?

If we ignore risk as a parameter for asset allocation, the optimal portfolio for most people probably would be a 100% stock portfolio. Because (this is probably not a surprise!) a 100% stock portfolio historically has produced the best long-term returns. For example, from 1926 through 20212, the average annualized return of an all-stock allocation was 12.3%. A 100% all-bond portfolio’s return was roughly half of that—6.3%.

But risk is a significant factor in determining asset allocation. Back to our example: The all-stock portfolio’s return is less consistent—it had 25 years of negative returns (out of 96) compared to 20 for the all-bond portfolio. And, the range of returns is wider for stocks—from down 43% to up 54%. Conversely, bonds ranged from -8% to +46%—a much narrower range.

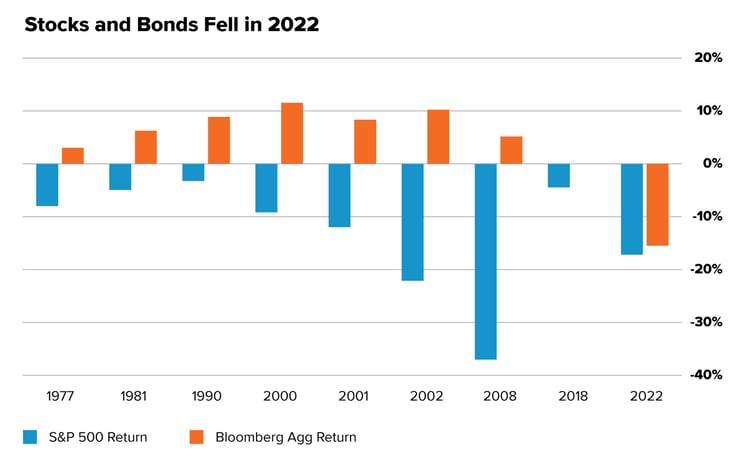

Sometimes, though, allocation norms go out the door. Last year was a case in point. For only the third time since 1926, stocks and bonds declined in the same year. Part of the reason for the connection was that U.S. stocks and U.S. bonds (both governments and corporates) have a high negative sensitivity to unexpected inflation. In other words, they both fall when unexpected inflation spikes.3

Source: Standard & Poor's, Bloomberg, L.P. Chart shows the performance of U.S. large-cap stocks (S&P 500) and U.S. corporate and government bonds (Bloomberg Agg) during down U.S. stock market years.

Source: Standard & Poor's, Bloomberg, L.P. Chart shows the performance of U.S. large-cap stocks (S&P 500) and U.S. corporate and government bonds (Bloomberg Agg) during down U.S. stock market years.

But getting asset allocation right is not just a decision between stocks and bonds. A host of sub-asset classes within each may be appropriate too. For example, there's a choice between large and small companies or ones in the U.S. versus those outside the U.S. Also, possibly selecting stocks that pay a regular dividend or bonds that pay a coupon. There are many choices—each with distinct characteristics that may make it appealing. Below we identify two we think are exciting sub-asset classes right now.

All of this shows that while asset allocation is important, there is no one right way everyone should follow. But there usually are choice combinations for certain situations. And understanding investor risk from three angles—propensity, capacity, and tolerance —is critical.

We highlight risk because when it is misidentified, investors tend to make rash decisions in the presence of adversity that often can negatively impact future wealth accumulation. In other words, during a strong up market, most investors tend to have the “I laugh in the face of risk” attitude and take on too much risk. But in a down market, they typically run for the hills—sell when stocks are down and hide their cash under a mattress. But after identifying and implementing the appropriate risk, investors often tend to be more comfortable with staying the course and riding the ups and downs.

Reevaluate stock positions

Holding the "best" securities outside asset allocation also contributes to returns. There’s a notion that investors should not sell their downtrodden holdings during a decline because they will lock in those lower prices and lose the opportunity to capitalize on a market recovery. That is a fair assessment and a time-tested strategy that works when they have time to wait for a market upswing AND they still believe in those companies.

But there is also a tactic of reviewing holdings, looking for previously unavailable opportunities, and cutting out dead weight when an investment thesis has changed. For example, in 2022, the speculative parts of the equity markets—those companies that were unprofitable primarily because they relied on cheap financing to grow their businesses but still bulldozed their way to high market valuations—repriced to reflect the true nature of their businesses. If those are in a portfolio, they’ve probably declined a lot. But should an investor continue to hold them? Maybe there’s a better option for those investment dollars.

In sum, locking in losses to sit on the sidelines will not allow that money to generate gains when the market turns up. But trimming or selling out of positions to upgrade to what is believed to be higher quality, long-term holdings is a tactic that can take advantage of current market conditions.

This refinement and selectivity are reasons why active managers have the potential to outperform during down markets. For example, one study found that more active funds outperform the least active ones by 4.5% to 6.1% per year in down markets after adjusting for risk and expenses between 1980-2008.

It also found that “the sources of fund performance suggests that active funds show better stock picking skills in the down markets.”4 Likewise, similar findings arose from another study of over 1,000 actively managed U.S. funds from 1995 through 2020. On average, they consistently beat the Russell 1000 index in falling markets. The top 25% of managers bested the market 60% of the time, while the top 5% topped the market 75%.5

Two interesting asset classes

In addition to active management, we believe these asset classes look particularly attractive: U.S. mid-caps and international stocks.

- Searching for growth: U.S. mid-caps

U.S. mid-cap stocks are nestled in a weird place between smaller, often nascent companies and larger, household-name companies. As a result, they often get lost in the asset allocation pie as many investors flock to the well-known names or try to hit it big with a small company. But mid-caps have a unique performance history in environments similar to today.

Over the last 25 years, mid-cap stocks have outperformed the large-caps in two of the previous three sustained rising rate periods, by 12.5% from 2004-2006 and 10.6% from 1999-2000. However, in 2015-2018, they underperformed by 4.7%.6

And during recessions, mid-caps also outperform their larger peers—by 5.1% during the dot-com bust and 5% during the Great Recession.6

Our take: We think mid-caps have two attractive advantages over larger companies. First, mid-caps are cheap right now. The relative valuation appears attractive—currently trading at nearly two standard deviations below large caps. Through the end of 2022, the S&P 500 (large-caps) was trading at a P/E of 20x, whereas the S&P 400 (mid-caps) was trading at 14.5x.7 This discount is often the case because historically mid-caps have tended to get beaten up more than large-caps during a downturn, so a reversion to the mean says they may have a higher return.

Second, we expect mid-cap earnings. Large-cap earnings fell 4%, while mid-cap earnings rose 11% in 2022.8 And what gives us comfort in 2023 is that mid-cap companies are more exposed to the healthier U.S. economy, unlike large caps, which have a higher exposure to overseas markets that are not faring as well, especially in Europe.

- Finding quality: International stocks

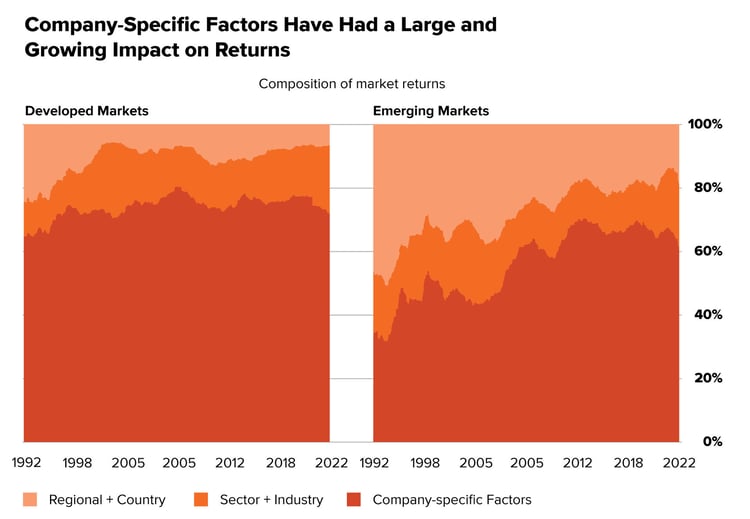

Quality companies are found all over the world. Unfortunately, U.S. investors often forget they can find good companies even in challenged overseas regions. This is especially true in developed markets, where company-specific factors tend to influence returns significantly more than the sector or region. But even in emerging markets, company-specific factors are growing more influential.

Source: Empirical Research Partners. As of Sept. 30, 2022. Analysis provided by Empirical Research Partners using their developed market and emerging market stock universes that approximate the MSCI World Index and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, respectively. Data show the percentage of market returns that can be attributed to various factors over time, using a two-year smoothed average. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

Source: Empirical Research Partners. As of Sept. 30, 2022. Analysis provided by Empirical Research Partners using their developed market and emerging market stock universes that approximate the MSCI World Index and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, respectively. Data show the percentage of market returns that can be attributed to various factors over time, using a two-year smoothed average. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

And like mid-caps, international equity is trading at a steep discount to the U.S. market. While that is not a new phenomenon, tailwinds such as the U.S. dollar, an easing of the energy crisis, and stabilizing geopolitical forces could help propel company earnings.

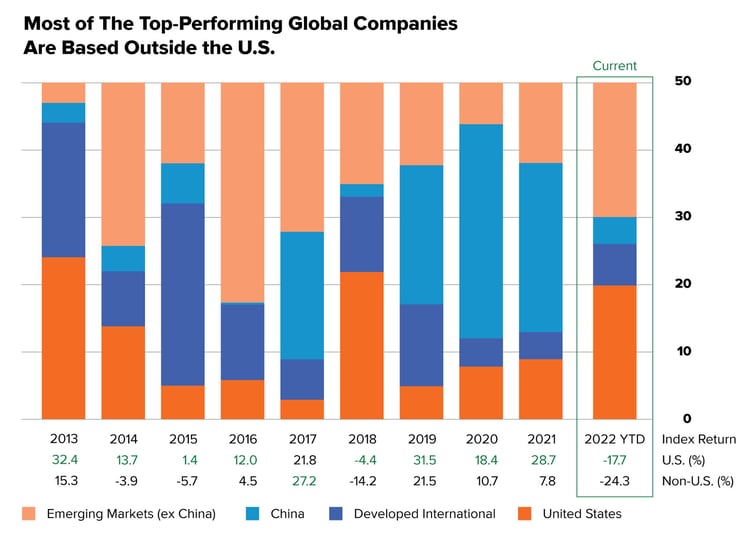

Another little-known fact is that three-fourths of the top-returning companies since 2013 are located outside the U.S. In 2022, many of those were in emerging markets (excluding China), while in the previous three years, Chinese companies were the drivers. So despite index returns favoring the U.S., high-quality companies exist outside the U.S. That is also why we believe a passive approach to international investing is probably not beneficial. Instead, it's all about stock picking—choosing the highest quality non-U.S. companies can potentially outperform many of the lower-quality ones.

Source: MSCI, RIMES. 2022 data is year-to-date as of Oct. 31, 2022. Returns in U.S. dollars. Top 50 stocks are the companies with the highest total return in the MSCI ACWi each year. Returns table uses E&P 500 and MSCI ACWI ex-USA indexes for U.S. and non-U.S., respectively.

Our take: When discussing mid-caps, we said that Europe is not doing well. That's true. But it doesn't matter. Because as we showed earlier, company-specific fundamentals, rather than geographic orientation, often drive returns. Thus, stock picking is critical.

It's also why considering a global equity fund where the manager can overweight more attractive geographies or companies takes the guessing game away from individual investors.

Additionally, since the U.S. dollar has remained strong for the most part (although it’s weakened recently) against other major currencies, many international stocks represent relative bargains and offer attractive returns for U.S. investors.

Lastly, growth expectations for this year and 2024 favor economies outside the U.S. For example, the forecasted 2023 real GDP (real growth—growth adjusted for inflation—is what you should look at with rising or high inflation) for the U.S. is 0.5%, which is slightly higher than Europe (0.0%) but far below emerging markets (3.4%), including China (4.3%) and India (6.6%).9 2024 forecasts follow the same pattern.

Short-sightedness may limit long-term growth

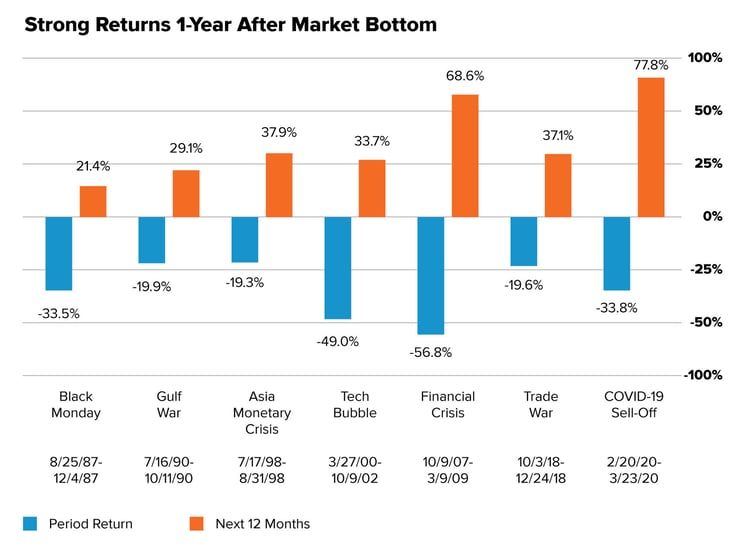

Investing in a down and uncertain market and economy is not easy. And unfortunately, neither we—nor anyone else—can forecast when the worst may be behind us. But what we hope we showed is that there are pockets of investments that may appear attractive. And if investors step back and view the entire market, history shows that times like today do not drag down markets forever!

Source: Blackrock. S&P 500 drawdown and total return from the market bottom.

Source: Blackrock. S&P 500 drawdown and total return from the market bottom.

Footnotes

1Vanguard, The Global Case for Strategic Asset Allocation (Wallick et al., 2012)

2Vanguard. Data for the U.S. stock market returns come from the Standard & Poor's 90 Index from 1926 to March 3, 1957, and the Standard & Poor's 500 Index thereafter. Data for the U.S. bond market originates from the Standard & Poor's High Grade Corporate Index from 1926 to 1968, the Salomon High Grade Index from 1969 to 1972, and the Barclays U.S. Long Credit Aa Index thereafter. Data for U.S. short-term reserves is from the Ibbotson U.S. 30-Day Treasury Bill Index from 1926 to 1977 and the FTSE 3-Month U.S. Treasury Bill Index thereafter. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. The performance of an index is not an exact representation of any particular investment, as you cannot invest directly in an index.

3WisdomTree, Bloomberg, S&P. Data from 1960 through June 2022. Sensitivities are -0.86 for U.S. Stocks (S&P 500 Gross Total Return Index), -1.32 for U.S. Treasuries (Bloomberg U.S. Treasury Total Return Unhedged USD Index), and -1.28 for U.S. Corporate Bonds (Bloomberg U.S. Corporate Total Return Unhedged USD Index. Unexpected inflation is the realized inflation rate minus the T-bill rate.

4“Do Active Funds Perform Better In Down Markets? - New Evidence from Cross-Sectional Study,” Zheng Sun, Ashley Wang, Lu Zheng*, August 2009

5Investment metrics, accessed January 17, 2023

6Ycharts. Dates represent the first and last Fed interest rate increase in each cycle. The S&P 400 index represents mid-caps, and the S&P 500 index represents large-caps.

7Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices. Actual data through Sep. 30, 2022. Estimated data through Dec. 31, 2022. Expected 2022 earnings data is estimated for 4Q22. Data downloaded on Jan. 11, 2023

8World Bank, Jan. 2023

Related Posts

3 U.S. Market Trends That May Help Build Wealth

Did the 2022 market decline sour you to investing in stocks? That’s understandable. Being trigger...

Could Quality and Growth Investing Lead to Faster Loss Recovery?

When most people shop for a big-ticket item—like a car, tv, or even a vacation—they fall along a...

Investing in Mid-Cap Stocks During Turbulent Times

Do you have mid-cap stocks in your portfolio? Maybe you don’t know because there isn’t a uniform...

Interested in more?

Get our popular newseltter delivered to your inbox every month.

Search the Insights Blog

How to invest with us

Click the button below to learn how you can get started with Motley Fool Asset Management